Ethnoconvenience: A Cousin of Colorism and Colorblindness and a Behavior of Tolerance and Exclusion-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Social Sciences

Abstract

Many organizations have instituted policies of

tolerance as official parts of their corporate or agency diversity and

inclusion initiatives, and

many people have become accustomed to using the term synonymously with

acceptance and inclusion. Tolerance, however, despite the likely

intended meaning of the term, is a white-centric artifact developed by

the empowered in a dominant-subordinated culture, with the word, at its

very roots, making the implication that people of color and other

minority groups are to be tolerated—accepted against the standards and

norms

in a culture of eurocentrism and racial privilege. Essentially,

attitudes, language, and behaviors of tolerance include a group of

behaviors, such as

colorblindness, colorism, sameness, centralization, credentializing, and

tokenization, among others, that espouse tolerance and therefore,

instead

of diversity, equity, and inclusion promote toleration and exclusion. We

introduce ethnoconvenience as one series of such attitudes and

behaviors

and define and describe what warrants ethnoconvenience and how it is

related to yet differentiated from the other language and practices of

tolerance in today’s immortalized dominant-subjugated U.S. culture.

Keywords: Ethnoconvenience; Tolerance; Racism; Prejudice; Diversity and Inclusion; Stereotyping; Racial Privilege

Introduction

Racial discrimination continues to be a problem in the United

States (U.S.) and globally. Despite great progress over several

generations, this pervasive problem exists in U.S. communities and

organizations and affects the way that people interact in public

as well as the way organizations are designed, developed, and

operated. Despite efforts to progress beyond them, there continue

to be issues related to race, color, and culture and they have a

significant effect on social and economic disparities and prevent

equity and inclusion. Government administrators, politicians,

academics, community leaders, and organizational executives

have worked to improve diversity programs and policies and

have created standards and policies designed to minimize or

exterminate marginalization. These efforts have increased hiring

of people of color globally and have prompted the addition of

language of tolerance into many organizational policies and

handbooks.

Unfortunately, many do not understand the implications and

ramifications of attitudes, language, and behaviors of tolerance

which, although designed to prevent bigotry and prejudice, act as

contributors to diversity and exclusion rather than inclusion and

equity. There are numerous behaviors that fall into this category of

tolerance, including one that we introduce that, although related

to the others, separates itself. This attitude and behavior is termed

ethnoconvenience, and it can promote, preserve, and perpetuate

inequality and exclusion in organizations, communities, and

society. The purpose of this article is to define, describe, and

exemplify ethnoconvenience and discuss how it is related to the

other behaviors and attitudes of tolerance, and to further explain

the role that it plays in the perpetuation of racial inequality and

exclusion in organizations, communities, and in society in general.

Racism, Inequality, Diversity, Inclusion, and Multiculturalism

The United States is a nation with a history of being strongly

preoccupied with differences, and thus diversity has very much

been a matter of identity in the country [1]. Our national construct

in the U.S. is one that has been defined as a continuum from a dominant versus subordinated culture towards multiculturalism,

equity, and inclusion [2]. Moving towards a healthy construction

desires the inclusion of subordinated groups, including categories

of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, citizenship status,

religion, and ability, and the intersection of these categories [2].

Unfortunately, we are not, as a nation, nor as a people globally,

nearing the terminal end of that continuum. Racism has deep,

and often horrific roots in the history of the U.S. and the national

population, and racism and inequality have long been and continue

to be a pervasive social problem in our society, in communities,

and in organizations, including occupational settings. It is no

secret that the dominant culture in a society, a community, or an

organization molds individuals, their attitudes, their beliefs, their

values, and their behaviors [3]. In the U.S., the predominant culture

of white dominance [2] has shaped the government, laws, social

groups, organizations, and the individuals within the population

for generations [4]. Certainly, many organizations have figured out

the economic, legal, and social benefits of and reasons to diversify

the workforce. These organizations have begun to understand that

they need to draw the best talent to remain competitive in today’s

rapidly changing global market and that this talent comes from

different demographics in the global population [4-7].

Nevertheless, we still dwell in a racially divided and

dominance-driven nation, and this is mimicked in organizations.

We must candidly and honestly drive discourse and dialogue and

strive not simply for tolerance, which is a byproduct of the raciallydriven

culture of dominance, but instead for racial equality, as well

as equity in the workplace. James Baldwin stated that the future,

and dealing with discrimination and diversity in the future, is

our responsibility because we are our only hope [8]. Therefore,

it is critical that we address the different language, practices,

pathways, and behaviors that continue to perpetuate racism,

bigotry, and the dominant-subordinated culture that exists in our

society. The word subordinated instead of subordinate is used

here because it is a condition that is forced upon the group by a

majority or dominant group historically empowered to do so [2].

We posit that a behavior, attitude, or practice, which we call

ethnoconvenience, is a distinct, though related, attitude and

behavior of tolerance [4,7], as will be discussed throughout the

manuscript, and thus is a significant contributor to inequality,

inequity, discrimination, and delegitimization, and is a barrier to

equality, inclusion, and multiculturalism.

Discussion

Ethnoconvenience – An Introduction

Within the problems and continual issues of prejudice and

racism in the U.S., one of the biggest purposes for and results

from bigotry is delegitimization, which is the categorization of

groups into negative social extremes that drive exclusion from

the dominant society’s definition of human norms and values [9].

Whether purposefully established and instigated, or accidental,

delegitimization occurs in society at the national, community, and

organization levels.

There are numerous stages in Huntley, Moore & Pierce’s

[2] continuum, representing the journey from racial inequality

to equity and inclusion, where delegitimization is clearly

identifiable. This continuum is a brilliant map of the U.S. social

system undergoing transformation, providing a better and more

transparent understanding of race dynamics. Combined with

the continuum, Huntley’s, Moore’s & Pierce’s [2] Journey of Race,

Color, and Culture explores the complex dynamics in the U.S. and

illuminates who we are, as individuals, and how we behave in the

context of these dynamics.

Although many are aware of the numerous methods by

which delegitimization occurs, and the ways in which racism

rears its ugly head, including stereotyping, white privilege, white

liberalism, colorblindness, credentializing, and tokenization,

among other behaviors associated with the supremacy-driven

concept of tolerance, one concept closely related to but separate

from these behaviors and attitudes is generally missed in the

discussion altogether. This behavior, although sometimes muted

in comparison, is no less damaging or problematic in the dynamics

of interactions that deal with the problems of racial inequality,

inequity, prejudice, and exclusion.

Ethnoconvenience is a close cousin of colorblindness,

sameness, colorism, tokenization, and stereotyping, all

attitudes and behaviors of tolerance rather than equality and

multiculturalism. In short, ethnoconvenience includes the

identification and categorization of individuals, and application

of values, thoughts, beliefs, and affiliations onto those individuals,

based on appearance and assumption. It is, in practice, a way of

categorizing someone because it is convenient to an argument,

proof of a point being made, or action. Ethnoconvenience, left

unattended, affords the perpetrator the ability to proceed with

thoughts, behaviors, or treatment towards others with little effort

or difficulty, and without alarm of inherent bias or racial privilege.

In order to thoroughly understand ethnoconvenience, it is first

vital to explore the different related attitudes, practices, and

behaviors of tolerance.

Attitudes, Behaviors, and Language of Tolerance

Tolerance is a term often used to define acceptance, and is

commonly referred to in educational, corporate, and government

agency policies and procedures in reference to ensuring inclusive

environments that are free of racism and bigotry. Nevertheless, the

use of the term tolerance, with reference to the social constructs of

race, identity, and societal race relations, is one that delays or halts

progress towards equity and multiculturalism, and may, on the

subconscious level, promote exclusion and continued bigotry [7].

Today, arguably a revived era of pseudo-normalized racial

and ethnic upheaval that is both a cause for and a product of

police brutality, bigoted demonstrations, riots, politicians’ racist

remarks, defacement of cultural landmarks, disparate treatment

in commercial establishments, and inhumane detention practices,

among others, it is not uncommon to hear subject matter experts,

reporters, politicians, and media pundits call for sensitivity training and increased tolerance in the general population or in

organizations.

However, the language and attitude of tolerance in these

pleas, as well as those commonly seen in human resources (HR)

policies and corporate diversity and inclusion (D&I) practices,

are examples of the perpetuation of this dominant-subordinated

behavior, where the mass population is the one that “tolerates” the

existence and practices of the “others,” the people of color (PoC).

Tolerance is a topic of race and power in society, in conjunction

with other identities and forms of discrimination [10], although it

does not always appear blatant or may not even be recognized by

the perpetrators, remaining purposefully or conditionally hidden

in their unconscious states, even as a positive instead of negative

social element [7].

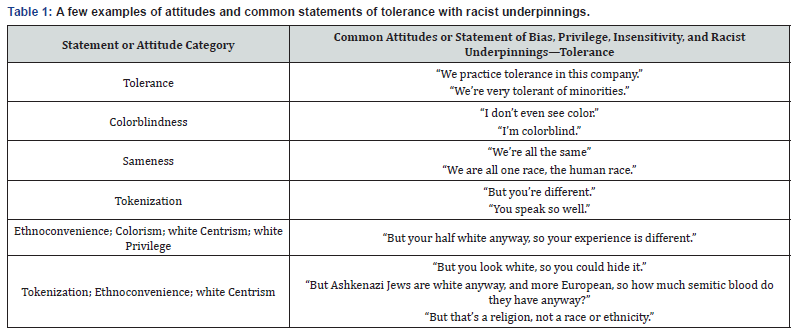

Although many corporations and other organizations have

taken to increasing and improving corporate social responsibility

(CSR) programs regarding D&I, many of the policies still tend to

result in attitudes and language that, even on subconscious levels,

result in behaviors and practices of dominance and subjugation

in organizations, providing advantages based on pre-established,

long-lasting, habitual and historic cultural artifacts of inequality,

including attitudes and common statements that foster or

perpetuate exclusion and marginalize or delegitimize PoC,

exemplified in (Table 1) [7]. As human beings, and particularly

those in leadership and other positions of influence in society,

we must recognize the effects of the tolerance practices of

colorblindness, sameness, tokenization, colorism, stereotyping,

white centrism, model minority status, and ethnoconvenience—

practices that perpetuate diversity and exclusion instead of

promoting diversity and inclusion. Practices that have been

normalized in the greater society in the U.S.

Colorblindness

A commonly heard response regarding racism is “I don’t

even see color.” While some believe that this is a commendable

statement or outlook, it is instead a contributor to the problem

of racial inequality. Being colorblind is not a solution for racism.

Being colorblind means that there’s a failure to identify and

recognize the person in question, thus ignoring or rejecting their

selves and all those traits and experiences that make them who

they are. By stating that one is colorblind, it is implying that

PoC are invisible to them, and this is a failure to recognize one’s

cultures, rites, rituals, upbringing, and experiences [2,4].

Colorblindness ignores cultural differences instead of

honoring them and allows people to ignore the history of white

cultural dominance and the experiences of PoC in dealing with this

subjugation throughout history. Although people that make these

statements may even believe that they are attempting to treat

everyone equally, the reality is that it perpetuates the dominantsubordinated

culture [2,7]. Colorblindness is one attitude and

behavior of tolerance and it exhibits a message of ignorance to

cultural differences, and even if unintentionally, it compares PoC

to white people norms, implying that PoC are tolerable rather than

equal [7].

Sameness

Sameness, closely tied to colorblindness, is another behavior of

tolerance. It is not uncommon for people to make race-associated

statements that imply that “we are all the same underneath.” Not

only is this biologically implausible, it immortalizes privileged

and bigoted thinking and behavior. Even people that have been

intimately involved in the struggle against bigotry and racism have

used these types of statements, probably with the best intentions,

but with a subconscious frame of privilege.

In a recent best-selling biographical novel [11], for example,

although we cannot presume what thoughts and ideas escaped the

author’s mind at the time of writing, there is a quote that states that

“we are all the same.” As explained, this language is problematic

for D&I scholars, applied behavioral scientists, and social science

practitioners who focus on D&I. Like colorblindness, sameness

is a concept that perpetuates the dominant-subordinated culture [2,4]. In the context of the statement that “you’re no

different than I, we are all the same,” sameness practically means

whiteness because it positions PoC in white cultural norms, as

though they are tolerable now that they have reached the level

of white standards and have been proclaimed to be “the same.” It

discounts the cultural differences and discards experiences with

racial injustice and bigotry [2], delegitimizing the struggle. Thus,

statements and attitudes like these ignore the uniqueness of our

race-based differences, instead discarding the differences we have

in upbringing, life experience, rites, and rituals for a proclamation

that “you are as good as I am” [7].

Colorism

Colorism is a persistent problem for PoC in the U.S., and

globally, although it is much less focused on in race discourse.

In general terms, colorism, which is also sometimes referred to

as skin color stratification, is a means by which prejudice occurs

not solely based on race and ethnicity, but also on skin color and

tone, and other allelic features. In many aspects, this behavior

privileges lighter skinned PoC over those with darker skin and has

been shown to sometimes cause disparities among people of the

same racial background in terms of income, education, housing,

employment, and organizational positionality [12]. Historically,

the social construct of racism has permitted the dominant culture

to not only unequally treat PoC based on race, but also on skin

color and darkness, furthermore, creating tension within and

between communities of PoC [12]. This behavior has not only

perpetuated white privilege and racial bigotry against PoC, but it

has sabotaged unity and solidarity between inter- and intra-PoC

groups, like the effects of the social construct of model minorities.

Some research shows that PoC with lighter skin have, as a

result of white supremacy and white centrism, enjoyed some level

of clear advantage when it comes to economics, employment, and

educational disparities, marginalizing individuals with darker

skin and limiting opportunity. However, the data also shows

evidence of a disparity regarding ethnic authenticity, recognition,

and legitimacy, on the contrary being granted to individuals with

darker skin, marginalizing and delegitimizing lighter skinned

individuals and minimizing their experiences and cultural

identities. This practice of colorism is directly related to and part

of the larger problem of systematic and systemic racism, both in

the U.S. and globally [12], and is a creation of white supremacy and

the racist culture in U.S. history.

Although this racist phenomenon against PoC has occurred

throughout generations in the U.S., it has somehow gone undetected

in the legal and policy infrastructure. In the U.S., colorism is often

ignored in the courts as a type or kind of discrimination [13]

because although the law includes color as a basis for prohibited

discrimination, it has generally been interpreted to mean the same

thing as race [14], not including hue, tone, hair color, hair texture,

and eye color, among other features.

Colorism expands bigotry from the dominant to the

subordinated, turning people of color against one another as a

result of skin shade, and based on a eurocentric, white idea of

beauty and acceptability. Under generations of exposure to this

behavior, Black, Asian, and Latino/a people, among others, have

had some of their experiences trivialized and their opportunities

minimized.

Hidden or Implicit Bias

Hidden or implicit biases are automatic, unconscious or

subconscious preferences for or against a group or individual.

Although implicit biases are not always negative, these preferences

act to form the basis for related behaviors – stereotypes,

discrimination, and prejudice. Thus, hidden or implicit biases

can feed the racially-based disparity in communities and in

organizations [15].

These implicit biases affect people’s actions and decisions in

an unconscious or subconscious manner, with the perpetrators

often unaware of their privilege or any intention of control [2],

and white privilege often precludes people from recognizing

and understanding these hidden biases [16]. Even upon limited

recognition of these biases, individuals may still be hesitant

to admit that they hold them, often due to personal fragility

regarding being viewed in a negative manner [17]. As an outcome,

these biases lead to a detachment between intentions and actions,

as well as to the inability to address how the biases impact

interactions with others in organizations, communities, and

societies [7]. Implicit biases can cause people, including group,

organizational, or community leaders, to believe that they are

being inclusive and accepting of diverse people, diverse thought,

and cultures through their policies and practices of tolerance

when, in fact, these policies, practices, attitudes, and behaviors of

tolerance are exclusionary and prejudiced [7].

white privilege

white privilege is another relevant factor in the inequitable

and disparate practice of tolerance. It is defined as unearned

advantage gained for no other reason besides being white in

a white-dominant and homophile civilization. This is a strong

example of institutional power in a racially stratified society that

goes largely unacknowledged to many within that society. white

privilege is a crux to this dominant-subjugated culture that has

historically had and continues to employ a power-over instead

of a power-with relationship about PoC. This privilege has a

confirmed effect of forced societal dominance [18], putting PoC in

subordinated and unequal statures [2] relative to white society.

white privilege is commonly accompanied by resistance and

denial from those that benefit from it – even unconscious denial of

social favor and the advantages that come with it. The resistance

of people to consciously acknowledge this is evidence of how,

intentionally or not, power, privilege, and comfort have come to

non-PoC, and it benefits them to hold on to it [2].

Tokenization

With the practice of privilege and implicit bias in place,

tokenization is seeded as a relevant behavior and practice, exhibited also as a behavior and attitude of tolerance. This

behavior occurs or is displayed when individuals from a PoC

group are given honorary status within the white group. It is not

uncommon to hear from people, when confronted with some act

of racism or bigotry, that “I’m not racist, one of my best friends is

Black,” or a similar statement. Having a friend or an acquaintance

that is Black, Jewish, Mexican, Chinese, or disabled does not only

not automatically clear someone from being bigoted against those

racial, ethnic, or other groups, it displays a level of ignorance and

privilege, and can be argued to be an exhibit of the individual’s

prejudice.

Often, tokenization exists because a person from a different

demographic is allowed into the societal circles of the dominant

group within the dominant-subjugated culture, at least

superficially, because they present themselves in a way that is

acceptable to or tolerated by that dominant group, despite their

differences [2,7]. In short, this attitude and behavior consists of

granting honorary status to select individuals from an out-group

into the in-group based on acceptability to and adoption of the ingroup’s

social norms, although it often comes with the expectation

that those tokenized individuals put on airs [7].

Tokenization is often used as a multi-faceted approach to

benefit the in-group or individuals in the in-group. It allows the

members of that group to set aside their guilt and feel good about

their selves for accepting someone Black, Latino/a, Jewish, or

Asian, for example, into their group. At the same time, justifications

are often made for these “honorary” members. Announcing

that “they’re different,” of course describing difference from

others in the out-group rather than honoring the differences

from those in the in-group. Plus, this tolerance often comes with

additional expectations of not only falling in line but exhibiting

loyalty by using the honorary status in order to keep those in the

subordinated group “in their places [2].”

Tokenization does, by means of definition, exhibit acceptance.

However, this is not an inherent acceptance based on equity, and

can be termed modern-day acceptance, meaning that the individual

is accepted into the mould and is given a title of equal dependent

on the evaluation against dominant-driven, pre-determined

standards, in this case, white standards [7]. This modern-day

acceptance means that the vision of equality and justice is based

on white-centric standards rather than being inherently equal

based on humanity. This, of course, is not equality and equity, but

rather a faux acceptance and an attitude of tolerance, preserving

the power-over model and historic dominant-subordinated

culture.

Stereotyping

Stereotypes and prejudice are influenced by both individual self

as well as social motives, the perceiver’s focus of attention, group

membership, and the configuration of stimulus cues. Individual

characteristics of members of groups have shown to influence

the extent to which stereotypes and prejudice are activated, and

the extent to which they are automatic [19]. Effectually, the study

of stereotypes is the study of many aspects of social psychology,

including group membership, intergroup relations, and group

dynamics, as well as neurobiology and neuropsychology.

However, from a fundamental perspective, stereotyping requires

an understanding of human nature, particularly relevant to

neurocognitive fundamentals [20]. Psychologists have shown the

relationship between both neurocognitive and social dynamics

that participate in the formation of stereotyping. Stereotypes

are beliefs, regardless of accuracy or truth, about another group

in terms of personality, attributions, or behaviors. They are

often based on prejudicial thoughts and beliefs, and often create

negative attitudes toward those groups – attitudes that express

negative affective or emotional reactions [9,21].

It is through a lack of knowledge or understanding that

prejudicial stereotypes often form, and it is often through

experiences with an individuals or small samples that stereotypes

are generated and inaccurately applied to entire groups.

Unfortunately, these stereotypes can lead to learned reactions

and behaviors that are unjustified, such as disparity and inequity

in law enforcement and judicial action, employment interviews,

workplace promotions, banking decisions, property rental, and

educational opportunities, among others.

Behaviors and Human Factors Contributing to Ethnoconvenience

Visual Assumption

People are quick to make visual assumptions or to deduce

conclusions based on what they see immediately in front of them.

They often act based on these visual experiences or the visual

evidence before them. Although what they see may be true to

them, these so-called truths are directly based on their personal

experience and social construct, depending heavily on culture,

upbringing, training, experience, socialization, politics, and other

factors. But these assumptions and so-called truths are often

not evidence-based, and are even decided upon very simplistic,

rudimentary observational behavior.

Amy Herman [22] explains in Visual Intelligence how

individuals often make decisions based on assumptions that

they believe are evidence-driven because it, whatever it may

be, is occurring or has occurred directly in front of their eyes.

However, Herman explains that most people may observe, but

do not truly see what it is that stands before them. They make

assumptions and deductions without getting a deeper look at

and understanding of scenarios that transpire right in front

of them. These assumptions are often inaccurate, wrong, and

potentially damaging to investigations, interactions, relationships,

organizations, or communities. Such is also sometimes the

case regarding people. People are often perceived solely based

on visual assumption, without a deeply rooted knowledge or

understanding of their background, both physical and social. This

type of behavior often contributes to stereotyping and serves as a

base for ethnoconvenience.

Inattentional Blindness

As fore-mentioned, Herman [22] discusses the idea of visual

intelligence not as a means of exploring more than what people

see, but rather to take a deeper dive into what is right in front of

them, to analyze the scenario from every angle, and to pull new

or more detailed meaning from it, thus better observing their

situations and finding, describing, and defining the fine data

[22,23], and not making assumptions and deductions that are

emotion- rather than evidence-based. Very often, people see the

scenario or surroundings that are right in front of them, but do not

see or interpret the details in the scenario or the picture.

This inability to truly see what is directly in front of them

is termed inattentional or unintentional blindness. This

inattentional blindness phenomenon suggests that when focus

is placed exclusively on a specific part of a concept, behavior,

or image, the other details tend to fade into the background,

regardless of whether they are in plain view [22], and decisions

are made based solely on what one sees or perceives, regardless

if it is real. Furthermore, most people do not believe that they

experience inattentional blindness because they lack the

awareness of it and they lack, as fore-mentioned, the personal useof-

self-as-instrument skills to recognize this [22,23]. Combined,

visual assumption and inattentional blindness create a lattice for

stereotyping and ethnoconvenience.

Ethnoconvenience: Cousin to Colorblindness and Colorism

The practice and language of identifying someone based

solely on thoughts, beliefs, ideals, perception, interpretation, and

visual appearance, and to make assumptions regarding beliefs

and acceptable behavior based on those characterizations is what

we define as ethnoconvenience, because in a multitude of ways,

it enables the perpetrator to view the individual however it is

convenient for him or her, making assumptions based on the selfmisplaced

internal conveniences.

In short, ethnoconvenience can be interpreted as the

perceiver’s cognitive laziness in the management of potential

complex reality or data. The practice of ethnoconvenience ignores

data that is either unavailable, unseen, unknown, or uncomfortable

and instead makes determinations, definitions, and decisions

based solely on assumptions that are in fact based on personal

experiences, beliefs, or ideas. These beliefs and ideas may originate

from the fore-mentioned behaviors of tolerance, including white

privilege and implicit bias, as well as the related colorblindness,

sameness, colorism, and stereotyping. Based on these biases and

beliefs, individuals often commit ethnoconvenient behaviors and

categorizations as a result of the integration of visual assumption

and inattentional blindness. Ethnoconvenience can take many

shapes and forms, and they are all related yet slightly separate

or different from the other attitudes and behaviors of tolerance.

Multiple examples are provided in the following text, but this is

not an all exhaustive list or exhibit.

One example of ethnoconvenience includes the basic

categorization of an individual’s race or ethnicity simply based

on their physical feature appearance, including skin color, hair

color, hair texture, eye shape and size, nose shape and size, among

other features. For instance, assuming someone is of white race

or ethnicity because of their skin color, and either avoiding

the possibility or ignoring the knowledge that the individual is

Jewish, is an example of ethnoconvenience. A similar example

is assuming that a Black individual is racially white due to the

outward appearance of light skin tone, blonde hair, and green

eyes. Although this is ethnoconveniencing, this is the simplest

form. People make determinations based on observation, and it is

not always easy to identify the race or ethnicity based on physical

features. Many people could make this mistake, and it is often

human nature to do so.

On the other hand, knowing that someone is Black, Jewish,

Native American, or other background and ignoring that

information because of their outward appearance is not as simple,

and is a blatant act of either white-centric tolerance or intolerance.

This is the second type or example of ethnoconvenience. This

is either ignoring the race, ethnicity, or culture that you know

exists, or ignoring what is observable. For instance, identifying

an outwardly appearing Orthodox Jew as White, despite facial

features and cultural dress, or failing to identify someone who

is Black Hispanic as such, paying attention only to the black skin

color and ignoring the Latino/a race and culture of the individual.

A different example of this, though more difficult to identify, is

the assumption that family members are not related because

of skin color differences, such as making the assumption that a

darker skinned Black woman is a nanny or a babysitter when she

is caring for a lighter skinned or white skinned child, ignoring the

possibility or even the likelihood that she is the child’s mother.

A third type of ethnoconvenience involves ignoring or

devaluing an individual’s race, ethnicity, or culture because of

existing data. For instance, knowing that someone has distant

Apache or Navajo ancestry, but dismissing or denying that tie

because it is distant or low percentage. A similar example has to

do with the knowledge and understanding that an individual is

Jewish but ignoring or dismissing the genetic-racial and ethnic

heritage information and categorizing ethnic Jewry solely as

religious, and the individual based on skin color. Often, this is done

for convenient purposes in a debate or to attempt to prove a point,

and thus, the perpetrator conveniently ignores or dismisses ethnic

or cultural belonging for political or other gain, such as arguments

regarding indigeneity to a land or region.

The next example of ethnoconvenience is closely related to

colorism and stereotyping and may, but should not, be confused

with colorism. As fore-mentioned, peer-reviewed study data has

shown disparities between lighter and darker skinned individuals

of different races. The data has shown that some lighter skinned

individuals may have experienced economic, educational, or

employment advantages over PoC with darker skin, and that some

darker skinned individuals may have experience more acceptance and been credited with a higher level of ethnic authenticity and

legitimacy than their lighter counterparts [12,14]. Although these

study data may be true, the white-centric assumption regarding

these experiences is not colorism, but rather ethnoconvenience. In

other words, the assumption that someone of lighter skin has had

an easier experience or has not experienced discrimination at the

same or at any level is ethnoconvenience.

A further and related type of ethnoconvenience also having

to do with colorism and stereotyping has to do with applying an

assumption of appearance on an entire race, ethnicity, or culture.

While stereotyping generally has to do with applying experience,

observation, or knowledge of personality, attributions, or

behaviors of an individual to an entire group, ethnoconvenience

has to do with applying what one believes of an entire group,

regarding appearance, to every individual. An example would be

to assume that all Mexican people are Hispanic, or all Jews are

white, ignoring the diversity of the ethnic Jewish diaspora, such

as African, Latino/a, Sephardic, or Mizrahi Jewry, or that there are

Native American Mexicans that do not have Hispanic origins.

The above is not an exhaustive list and does not constitute every

type or example of ethnoconvenience, but rather provides some

examples. It is evident from these examples that these are usually

related to visual assumption and inattentional bias, as well as with

colorblindness, colorism, stereotyping, and implicit bias, and as

such, they are examples of attitudes or behaviors of tolerance that

can create intolerant environments. Ethnoconvenience can lead to

numerous social ramifications and can affect victims of its practice

in numerous ways.

Ignoring an individual’s ethnicity, race, culture, and identity

can leave those individuals feeling misidentified, misunderstood,

and insulted, and the ethnoconvenient acts of purposefully

dismissing an individual’s race, ethnicity, or culture can create

a negative, dispute-like, clashing relationship. Additionally, the

failure to identify and the blatant mis-categorization of individuals

can leave them feeling marginalized and delegitimized. People are

proud of their heritage, culture, and background, and strongly

identify with their races, ethnicities, and cultures as major

definitions of their selves [24].

Ethnic pride and belonging are two main parts of ethnic

identity, so it is not unlikely that separating or questioning

people’s identity from their present beings can affect feelings of

pride and belonging and cause problems for the individuals, and

for the group or organization that they belong to or interact in.

These practices and behaviors of ethnoconvenience, whether

blatant, inattentional, or implicit, can thus serve as tools of

deculturalization. Furthermore, mistaking, avoiding, ignoring,

or dismissing people’s races, ethnicities, and cultures can place

them into different identity groups, and potentially into the whitecentric

dominant group in the dominant-subjugated culture—a

group to which they do not belong or did not extensively

experience through life, thus creating unwanted tokenization or

forced social assimilation.

Ultimately, ethnoconvenience places an incorrect, false, or

incomplete identity on PoC as a result of assumptions made

under implicit bias and white privilege for convenient personal,

group, organizational, or political agendas, among others. This

results in identifying people incorrectly, often as white, and either

misplacing or minimizing their experiences, their individualities,

their identities, and their struggles. It is understandable how

ethnoconveniencing people and misidentifying them as white,

model minority, or dominant-belonging serves to delegitimize

their identities and their struggles in national dominantsubjugated

environments. Altogether, these behaviors can have

a social and psychological effects on individuals and create

feelings of denigration, like other types of racist or racially-driven

behaviors do.

Conclusion

Racism has been a pervasive problem over the course of

history in the United States. Even with great progress over

generations, there continue to be issues related to race, color, and

culture and a continuing disparity regarding equity and inclusion

based on race and ethnicity across the nation, in communities

and in organizations. Despite the progress made, the dominantsubjugated

culture is perpetuated, and as a result as well as a

cause for perpetuation, certain attitudes, language, and behaviors

termed as tolerance, masqueraded as positive movement towards

equity, inclusion, and multiculturalism, are attitudes and behaviors

that preserve, promote, and propagate inequality and exclusion.

Among them is the attitude and behavior of ethnoconvenience.

This manuscript defines the practice and behavior of

ethnoconvenience and exhibits how it is closely related to and

how it accompanies white privilege, hidden bias, colorblindness,

sameness, colorism, stereotyping, and tokenization, among

others, as an attitude, language, and behavior of tolerance,

where tolerance is a term of racially-driven exclusion. The article

provides examples of ethnoconvenience and identifies the effects

that ethnoconvenience has on individuals that experience it,

including insult, conflict, denigration, deculturalization, and

delegitimization.

Comments

Post a Comment