Developing a Strong HRM System: The Role of Line Managers-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Social Sciences

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to examine the line

manager’s role in developing a strong human resource management (HRM)

system which is distinctive, consistent and consensual. This paper

explores the process and outcomes of the line managers implementation of

a high performance HRM system in an Irish knowledge intensive firm.

Design/methodology/approach: This study is

based on interviews with senior management, HR director, line managers

and front-line employees in an Irish organization.

Findings: The findings show support for the

important role of line managers in implementing HRM systems to develop a

strong HRM system in the organization. However, there is inconsistency

across line managers’ communication and implementation of the new system

resulted in confusion and frustration among their respective

subordinates.

Practical implications: HRM professionals need

to be aware of the important role of line managers in promoting a

strong HRM system in the organization. In a knowledge intensive firm,

where agility and flexibility are essential, different departments may

require different nuances to an HRM initiative.

Originality/value: This study contributes to a

better understanding of the HRM implementation process in a

knowledge-intensive firm in Ireland, by using the HRM system strength

model as the theoretical basis for analysis and discussion.

Keywords: HRM System Strength; HRM, Case Study; Knowledge-Intensive Firm; HRM Implementation

Introduction

During the past few decades, the impact of strategic

HRM (SHRM) practices on organizational performance [1,2], in both

manufacturing and knowledge intensive firms, has gained extensive

research attention. For example, high performance work systems (HPWS)

including selective recruitment, extensive training and development

programmes, competitive compensation and benefit packages, participation

and information sharing, have been widely found to positively link to

firm performance. These ‘intended’ HRM practices consist of the HRM

policies and practices designed by the HR professionals in order to

align with business strategy [3-5].

Recently, scholars argue that it is not enough to

have these practices or policies in place rhetorically; only when these

practices are implemented, mostly by line managers, can these practices

create value for the organization [6]. This is when the ‘intended’ HRM

practices become the ‘actual HRM’ practices [5]. In implementing HRM

strategies, line managers have the dual responsibility of managing

individual employees’ work-related activities and playing a vital role

in transforming strategic human

resource management initiatives into practice in the organization

[6-12].

They are both ‘employee advocate’ and ‘HRM business

partner’ [13]. The increasing HRM responsibility facing line managers is

noted in the literature Edgar, Geare and O’Kane (2015) Larsen and

Brewster (2003). However, how line managers implement HRM has not been

given enough attention Brewster et al. (2013). In order to enable a

smooth transition from organizational to employee perceived HRM [5],

organizations need a strong HRM system, where all levels of employees

share collective perceptions, attitudes and behaviors [14]. To build a

strong HRM system and shape employees’ perceptions of the new HRM

system, line managers are the key agents in their capacity to send HRM

messages and to implement HRM practices [8,9,15].

This paper examines how different

intra-organizational players – senior managers, the HRM manager, line

managers and front-line knowledge workers - perceive the implementation

process of a new HRM system. The role of each of these in the

implementation and ‘actual HRM’ of a new HRM system, in this case, a

high-performance work system (HPWS) in a knowledgeintensive

firm (KIF) in Ireland, is analyzed, particularly focusing

on the line manager’s role and how this is perceived. The study

contributes to the research gap on the HRM implementation

process by applying the HRM system strength model [14] to

qualitative interview transcripts collected in an international

KIF based in Ireland. Our study integrates views from multiple

stakeholders in order to ascertain gaps in the distinctiveness,

consistency and consensus features of a strong HRM system [14].

In particular, the relationship between the line managers and the

employees is considered, in line with studies by Bos-Nehles and

Bondarouk [15], Bos‐Nehles, Van Riemsdijk & Kees Looise [8], and

Kilroy & Dundon [9], that explored the employees’ perceptions of

line managers’ intentions, performance and styles.

Research Context: Knowledge-Intensive Firms

Knowledge-intensive firms (KIFs) have been defined as those

firms where work is primarily intellectual and analytically taskbased;

where jobs are not highly routinized and involve some

degree of creativity and adaptation to specific circumstances;

and where the workforce consists of well-educated and qualified

employees to carry out the tasks and jobs successfully [16-18].

Examples of KIFs are high-technology, R&D-centred companies,

management and IT consulting firms. KIFs operate in a dynamic

and highly competitive environment Alvesson (1995) (2001).

Products and services are more complex, and the rate of

competition has accelerated, with shorter life-cycles [19] which

require constant adaptability. The telecommunications industry is

a prime example of an industry where competition has accelerated.

The increasing use of internet-based calls, e.g. Skype, Voip

(voice over IP), have raised the pressure for the telecommunications

industry that provide landline and mobile phone services. In

addition, customers’ phone usage has evolved from making

phone calls to sending texts/messages and to “eating data”, which

creates new opportunities and challenges for service quality, and

new pricing models. How telecommunications operators cope

with these challenges and achieve competitive advantage is a

timely question, not only for the telecommunications industry,

but also for other knowledge-intensive industries. This paper

explores data from an Irish case study organization within the

telecommunications industry.

Conceptual Framework: Strong HRM System

A strong HRM system can ‘help explain “how” HRM practices

lead to outcomes the organization desires’ [14]. In linking

organizational climate and organizational effectiveness, Bowen

& Ostroff [14] HRM system strength construct presents three

main features which together will impact upon employees’ shared

perceptions of the organizational climate, in turn influencing

organizational effectiveness. These three main features are:

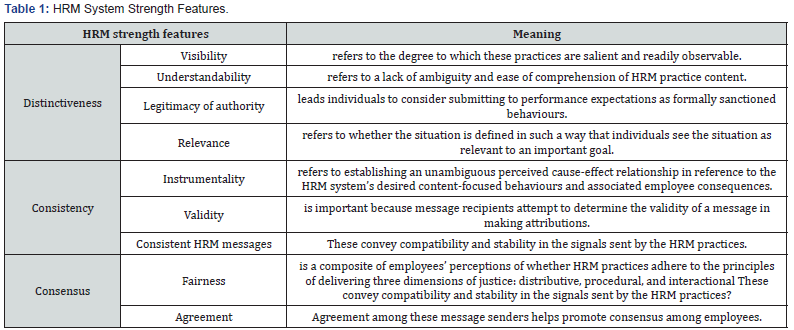

distinctiveness, consistency and consensus. (Table 1) presents and

describes the main features and their respective meta-features for

a strong HRM system based on Table 1.

HRM Distinctiveness

Four meta-features form the distinctiveness feature of a

strong HRM system, i.e. visibility, understandability, legitimacy

of authority, and relevance [14]. Visibility refers to HRM

practices that are salient and readily observable for employees.

Understandability refers to a lack of ambiguity and ease of

comprehension of HRM practice content. Legitimacy of authority

leads individuals to consider submitting to performance

expectations as formally sanctioned behaviors. Relevance refers

to whether the situation is defined in such a way that individuals

see the situation as relevant to an important goal.

HRM Consistency

Consistency, according to Bowen & Ostroff [14], mainly refers

to establishing consistent relationships. Consistency of HRM has

three meta-features: instrumentality, validity, and consistent HRM

messages. Instrumentality refers to establishing an unambiguous

perceived cause - effect relationship in relation to the HRM

system’s desired content-focused behaviours and associated employee consequences. Validity means that the HRM practices

can achieve the goals planned during the designing stage of such

HRM practices. Consistent HRM messages refer to the stability in

the signals sent by the HRM practices.

HRM Consensus

Consensus of HRM practices refers to the agreement among

employees regarding the intended targets of the HRM system. Its

two meta-features are fairness and agreement. Fairness of the

HRM system is a composite of employees’ perceptions of whether

HRM practices adhere to the principles of delivering three

dimensions of justice: distributive, procedural, and interactional

justice [20]. Distributive justice concerns about the equality of

the outcome [21]. Procedural justice relates to the process or

mechanisms through which outcomes are decided rather than

the actual outcomes [22,23]. Interactional justice is concerned

with the interpersonal treatment people receive during the

implementation of the procedures [24].

Heffernan & Dundon [25] investigated employee perceptions of

the fairness of HR practices associated with the high-performance

work systems model. In their quantitative survey across three

organizations in Ireland, employee perceptions of distributive,

procedural and interactional justice mediated the relationship

between high-performance work systems and job satisfaction,

affective commitment and work pressure. The other metafeature

of consensus is agreement which refers to the agreement

among principal HRM decision makers, e.g. HR professionals, top

management team, and line managers. We expected this aspect,

agreement, to be particularly interesting in our analysis of the

multi-stakeholder qualitative interviews with senior managers,

the HR director, line managers and employees in a KIF in Ireland.

Line Managers’ Role in HRM Implementation Towards Building HRM System Strength

The majority of SHRM research has focused on organizational

HRM policies and practices [26]. Some researchers argue that the

focus on the design of HRM policies and practices is not enough,

as it is only when these are implemented appropriately that they

can create value for organizations [5]. Wright and Nishii [6] have

labelled the implementation of HRM practices as ‘actual HRM’.

The key agents for implementing HRM are the line managers

who interact with front line employees in a frequent and timely

manner. Line managers have HRM responsibilities Alfes et al.

(2013) by virtue of their frequent and direct interactions with

their team members and subordinates.

In project-based organisations, for instance, the project

managers, supervisors or assignment managers are not only

responsible for project-related work (e.g. analyzing project needs,

allocating workload, monitoring project progress, completing

project reports), but also are responsible for team management

(e.g. analyzing training needs, informing subordinates of training

opportunities, managing individual performance, providing

feedback, promoting participation) Keegan, Huemann and

Turner (2012). The line manager’s role in the implementation of

people management practices is of critical importance in shaping

employees’ perceptions, experience of and attitudes towards

their work and organization [27]. A collective perception of HRM

practice is expected where employees share similar experience

of the work practices and have the behaviors desired by their

respective organizations, i.e. a strong HRM system [14]. For the

organization and senior managers, line managers are important,

as they are the implementers of the organization’s HR policies

and practices, e.g. treating employees as resources and/or caring

about their personal experience at work [6].

For employees, line managers have been shown to play an

important role in how employees experience their work [28-31].

How line managers implement HRM practices has implications

for how employees perceive and align with those practices. In

other words, the strength of the HRM system is heavily dependent

on the line manager’s role. The line manager’s key role in the

implementation of HRM has received increasing attention due to

their relevance in creating a strong HRM system.

For example, based on a European dataset, Larsen and

Brewster (2003) found clear evidence of a greater assignment

of HRM responsibilities to line managers. Other studies show

that line managers play an important role in managing employee

learning and development Gibb (2003), attendance Hadjisolomou

(2015), voice Townsend and Loudoun (2015), conflict Saundry,

Jones and Wibberley (2015), and knowledge sharing MacNeil

(2003). These studies have provided valuable insights on the

impact of line managers’ implementation of HRM on different

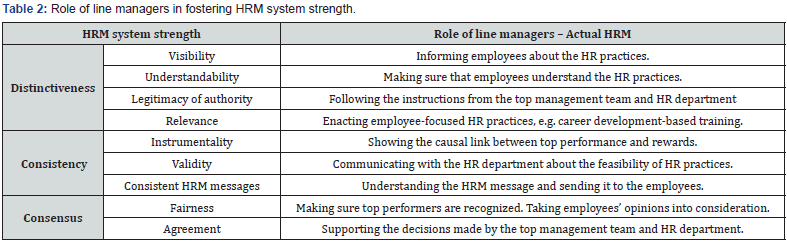

employee and organizational outcomes. (Table 2) shows the

expected line managers’ roles in promoting HRM system strength.

For the distinctiveness of the HRM system, line managers

play an important role in informing employees about HR

practices (visibility), explaining how these HR practices work

(understandability), following the instructions from the top

management and HR department (legitimacy of authority), and

demonstrating care for everyone, e.g. providing performance

feedback (relevance). For the consistency of the HRM system, line

managers need to show the causal link between top performance

and rewards (instrumentality). For example, line managers would

seek the opportunity to provide employees with recognition or

reward when they perform their work well or when they have

improved their work efficiency.

Line managers need to provide support for employees’

career development [32]. In addition, to achieve the validity of

HR practices, line managers need to communicate with the HR

department about the feasibility of the HR practices. In sending

consistent HRM messages over time, line managers need to

understand these messages and send them clearly to employees.

As line managers communicate with employees very frequently,

they know their subordinates’ needs and would be able to find the

best way to communicate the message to them more effectively.

The last feature of HRM system strength is consensus including

fairness and agreement. Fairness covers distributive, procedural

and interactional justice. Research shows that the manager can

make a large difference in affecting employees’ perceived justice

[33]. Line managers take charge of distributing work, content

and resources. Their decisions on these aspects are critical in

the formation of employees’ psychological contract, which is an

unwritten contract between employees and employers [34] trust

[35,36] and commitment [37]. To ensure distributive justice, line

managers should make sure that employees’ work gets recognized

within and across teams. For procedural justice, line managers

should ensure that the resources are distributed openly and fairly.

For example, only those better performers receive rewards. For

interactional justice, line managers should listen to employees and

consider their opinions when making decisions. High agreement

requires line managers to understand, accept and promote the

specific HR practices among employees.

The focus in this paper is on unpacking the role of the line

manager as perceived by the line managers themselves, by the

employees (directly reporting to line managers), and by senior

managers (to whom the line managers themselves report), as well

as the HR Director.

Research Method

Case Organization Context

We undertook a single case study [38,39] within a knowledgeintensive

firm in Ireland, a division of a large multinational

organization, where the HRM initiative being implemented

by line managers was a change initiative (introducing a highperformance

work system throughout the organization). The

sample organization, Telecoms1 (pseudonym), is one of Ireland’s

leading telecommunications companies with over 1.5 million

customers. It runs 2G and 3G networks in Ireland. It operates a

Media mobile marketing division, supports a number MVNO’s

(Mobile Virtual Network Operators) and is home to an academy

for accelerating start-ups.

Telecoms1 employs over 900 people and has a retail network

in excess of 70 stores. It has been operating in Ireland for 17 years

and is part of an international group. However, despite being

a division in a multinational organization, Telecoms1 operates

as a standalone business unit in the Irish market, though the

parent is the ultimate budget approver and holds responsibility

for senior leadership appointments. In being a division in a

multinational organization, it could be that practices which are

successfully implemented in the Irish division may influence the

implementation of similar practices in other country contexts.

However, we did not focus on this in our study.

The current CEO was appointed in October 2011 following

previous senior positions within the group. Reporting to him are

five directorates: Business, Consumer, Marketing and Innovation,

HR, Finance & Technology. After the appointment of the new

CEO, Telecoms1 found itself suffering from the effects of the Irish

economic collapse, increased market competition and regulation

that was reducing revenue streams (roaming, interconnect etc.),

resulting in falling profits and market share. In addition, the

consumer wanted new devices, demanded new services and

technology advances. It was with this backdrop that Telecoms1

introduced a change initiative in 2012, its high-performance

work system model, where targets and metrics for employee

performance became paramount.

This HPWS Included Six Targets

a) building organizational resilience

b) delivering unreasonable ambition

c) clarity on what really matters

d) living high standards

e) having a feedback rich culture

f) being decisive and promoting better decisions.

The organization’s fundamental goal was to become a highperformance

organization.

To achieve these targets and the goal, the first key step that

the senior leadership team took was to launch a new employee

performance management model. This new performance

management model asked managers and employees to agree

with objectives that focused not only on the traditional whatactions,

but also on the how- behaviors. To achieve continuous

performance improvement, line managers were asked to evaluate

“what” employees have achieved to contribute to the company’s

objectives as well as “how” consistently the employee had

demonstrated behaviors. This study focuses on the design and

implementation stages of the new HPWS, and the process of its implementation as perceived by senior managers, the HR director,

line managers and employees.

Sample and Data Collection

Telecoms1 has relatively flat organizational structure. The

organization includes the senior management teams (including

the CEO and HR Director), line managers and front-line

employees. The aim of this study was to comprehensively study

the line managers’ role in implementing HRM practice in the

organizations, as experienced and shared by the line managers

themselves and by their superiors (senior management and the

HR director) and subordinates. Therefore, when designing the

study, we firstly mapped out the key organizational stakeholders

in this change management initiative. In this context, the designing

of the HPWS was led by the senior management team including

the HR Director, promoted by senior managers, and implemented

by line managers.

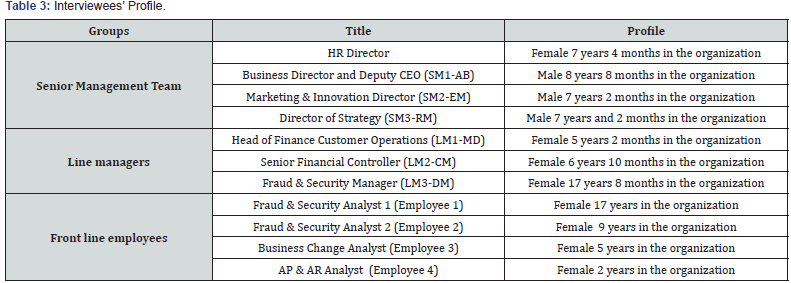

Therefore, we decided to select samples from these three

groups. The first author contacted all members on the senior

management team, and line managers and employees via

his network. To capture of implementation of the HPWS,

qualitative data was collected from senior management (three

Top Management Team Members and the HR Director), line

management (three-line managers) and the employees (four

front-line employees) via semi-structured interviews and a focus

group (with the employees only) in 2014, two years after the

change programme had been initiated. Each interview lasted from

30 to 60 minutes. Table 3 presents the interviewees’ profile.

We appreciate that the very limited number of interviews

conducted cannot be generalizable to all members of the

organization. However, the multi-level snapshot of the interviews

conducted provides an overview of the diversity of individual

players involved in a change management HPWS and shows how

agreement and consensus from Bowen & Ostroff’s [14] HRM

system strength framework is most challenging in practice.

The qualitative approach allowed us to gather descriptions

of the participants’ experience [40]. The participants were able

to express their views, opinions and values fully putting them

in the position of expert during the interview [41]. Respecting

the individual’s right to privacy was crucial and at no time

anybody was to feel pressurized or coerced into taking part

[42]. All participants were assured what they said would be

treated confidentially. A topic guide [43,44] was used in the

interviews, with all respondents asked to discuss the introduction,

implementation and the outcomes of the HPWS.

The interviews were semi-structured, ensuring that all the

topics were covered across the organizational levels, but that there

was flexibility for the respondents to speak about matters which

were not directly addressed on the topic guide [45]. In this way,

the semi-structured interview process facilitated the collection

of data on the same themes while also enabling an exploration

of issues across the respondents [46] on the introduction of the

HPWS.

The first author conducted the interviews. His role was to

inform the respondents about the purpose of this study, to assure

them of the anonymity of the study, and to confirm they were

comfortable to answer the questions. The interview was guided by

the interview questions. Respondents were given free rein to speak

about the topic from their own perspective. During the interviews,

respondents often addressed sub-questions in answering on a

topic which could enrich our understanding of their perceptions.

Data Analysis

All interview recordings were transcribed verbatim to

retain the integrity of the data [47]. Given that there were three

researchers involved in the study (authors), QSR Nvivo (version

10) was used in coding and analyzing the data. This system

enabled the researchers to review each other’s coding strategies

and validate them. The interviews and focus group data explore

the nature of the participants’ engagement, understanding

and actions they took in relation to the HPWS initiative in the

organization [46,48,49]. During the analysis of the data, the

interview transcripts were coded following the Bowen & Ostroff

[14] HRM system strength framework, with the interviews

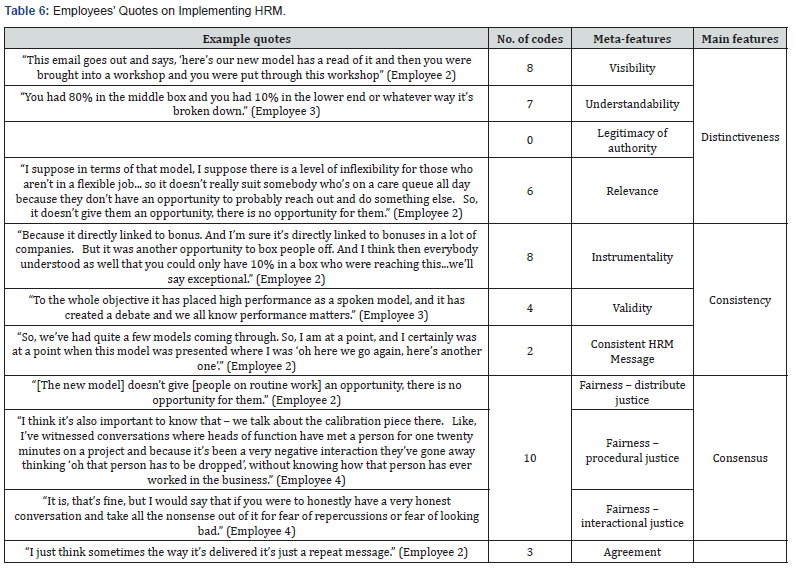

separated out across the intra-organizational levels of senior management, line management and employees (Tables 4-6). This

allowed us to capture the cross-level variation in terms of how

each level perceived the line manager’s role in the introduction

of the HPWS. The respective transcripts were read several times

and coded in line with the nine meta-features under the three

dimensions put forward by Bowen and Ostroff [14].

Findings on the Line Manager’s Role in Fostering a Strong HRM System

The need for the change programme in the KIF was outlined

previously. The HR Director sums this up as: “I think we had started

to accept a certain medal of mediocrity in the business” and a

change in the attitude and culture of performance was required.

Equally, the CEO (SM1-AB) felt that “at the time the culture was

very collaborative, collegiate, and team-focused – all good positive

stuff, but frankly maybe a little bit soft. And a little bit tolerant. So,

we felt there had to be a change in that…we did feel there had to

be a little bit more of an edge to why people were here, you know,

what they were doing. And just that culture, that performance

really mattered”. This distinctive appreciation that a change was

required was replicated across levels, with the line managers and

employees accepting the need for the change program and the

HPWS. As the HR director describes, gaining support from senior

management was the catalyst in ensuring the change program

would work:

“I knew once I got them the board into the right frame of mind

and if they were accepting of the model, then you could probably

overcome most challenges after that”. In this section we firstly

outline the line manager’s role, as described by the line managers

themselves, in terms of the strength of their implementation of the

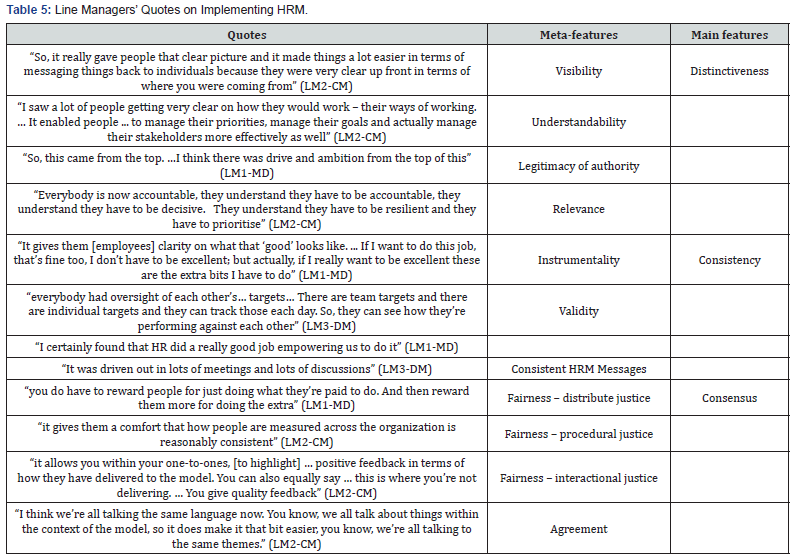

HPWS in the organization Table 5 provides some example quotes

here across the Bowen & Ostroff [14] HRM system strength model.

The richness of the data collected can be seen through the quotes

shared here Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, all the three main and nine meta-features

of strong HR system were covered by the line managers in our case

KIF in Ireland. Indeed, in our analysis across levels, we found that

all the features were present across each of the levels, suggesting

the foundations of a strong HRM system were present in the

organization. However, the legitimacy of authority (under the

Consistency dimension), and fairness and agreement (under the

Consensus dimension), were included less often in the narratives

concerning the HPWS introduction from the line managers.

Line managers acknowledge the drive for change initiatives

that needs to come from senior managers and then cascaded

down the organization. This support and buy-in from the top are

required in order to encourage the line managers to implement the HRM model (see following quote): “So this came from the top.

I honestly think that this was always going to be [that CEO] wanted

changes quickly. So, I think there was drive and ambition from the

top of this” (LM1-MD).

Senior managers also underlined the importance of the CEO’s

buy-in: “Because if the CEO doesn’t set the right example, well, the

management team doesn’t quite follow it, and then the next level

down doesn’t. So, I think he [CEO] has an extremely important role

as an example I think” (SM3-RM).

Reciprocally, the senior managers recognize the role of the line

managers in ensuring the successful implementation of the HPWS

system in the organization. This is reflected in the following quote:

“A lot ultimately depends on a person’s manager. ... The success

depends a lot

on the quality of the manager or how much they bought into

it. How much they

care about doing that kind of stuff. So, one of the challenges

we’ll always have

in any company is … you’ll have some managers who [are] just

… new

managers, they’re just learning to cope with the whole thing,

and whether

they’re able to really coach and help and bring on the people

they

have with them might be difficult for them. You have others

who are maybe just

not suited to the role” (SM1-AB).

It is also acknowledged that line managers need to mould the

implementation of the HRM model and to tailor it to their team. As

SM1-AB notes:

“in terms of how it is implemented and the more meaningful

conversations…

about …the value of what you’re doing and what you’re

contributing and how

it fits with your workloads and all that. So that’s where [line]

managers really

had to make a big difference”.

Similarly, by SM2-EM:

“One of the things that was really interesting was ... there was

a bit of a

diagnosis done around what is the challenge in each area. And

what

was going on in marketing was very different to business, to

technology and

finance, and we fixed our own house.”

We found that the process of implementing the model in

different teams was line manager driven, without any mention

of specific consistent supports for line managers in making

this happen, perhaps due to senior managers recognizing the

differentiated nature of different organizational groups and teams,

where a consistent approach would not be optimal.

The variation across line manager performance was noted by

senior managers. As SM2-EM states:

“it [the HPWS] allowed managers to call other managers and

go ‘well

hold on my team are doing that but your team aren’t’”.

Similarly, at senior management level the HR Director noted:

“They [employees] certainly heard everybody from directors to

managers talking about unreasonable ambition, it became a bit

of a buzzword probably around the place. …So, you would hear

certain buzzwords out of the model that were more pertinent

to some areas than others. But I think it depended on which

directorate you were in, which aspect of the model resonated most

with you.” (HR Director)

On the one hand the HR director acknowledges the variation

in the implementation of the HPWS in different departments by

different line managers (see above quote), while on the other

hand the HR director also appreciates that the aim of the HPWS

change program was to: “ignite a different era, a different culture;

a different way of thinking about the world and it was to unite

people’s innate ambition”. This shows the complexity of achieving

a strong HRM system in practice, where a strong culture and unity

within the department needs to be tempered with the requirement

for flexibility and agility of different departments with different

work outcomes and requirements.

Notably at the line manager level, it was apparent that

there was variation in the implementation of the HPWS across

departments: “I certainly found that there seemed to be a feeling

that people were throwing back to the old model where marking

somebody as ‘development’ was - you don’t want that person

on your team…It made me a little bit cautious about using that

so freely, because I had great people in there that I wanted to

encourage their development not see them… outside the door.”

(LM1-MD)

The employees agreed: “it’s like everything it comes back to

the managers” (Employee 2).

In addition, it was evident that not every role could achieve

“unreasonable ambition”, one of the aims of the new HPWS, again

underlining the variation between departments and roles within

departments.

The input from the employees to the system was perceived by

the employees as not being legitimized:

“what I think is a problem with the performance model in

terms of the fairness around it… I still think there’s a culture in

here of the manager comes along with your rating and that’s it...

Even though you fill out your objectives mid-year and year-end”

(Employee 3).

On the other hand, other employees felt empowered by the

new HPWS:

“I now [have] got an actual voice in this model” (Employee

1). This lack of consistency and consensus in how the employees

perceived their input was being received in the new HPWS,

coupled with the inconsistency in the implementation of the HPWS

in different departments, raises a challenge in how organizational

justice is perceived by the employees [14] consensus feature.

Knowledge workers like fair process: ‘When employees don’t trust

managers to make good decisions or to behave with integrity, their

motivation is seriously compromised’ [27].

In KIFs, the knowledge workers are the key source for new

knowledge generation, which, in turn, leads to the organization’s

success. Therefore, the employees’ input is particularly necessary

in KIFs. However, the involvement and realisation of knowledge

workers’ input into facilitating the successful implementation

of a HR strategy was not evident in our analysis. Indeed, at the

employee level, some employees felt that the model had already

been in place in some departments before its actual directed

implementation from senior management.

The following quote reflects this: “But I think before they came

in, our Manager kind of had us living it in a way didn’t she for a

couple of years before that? She was big into the high-performance

model and showing off what you’re good at and pushing that way.

… [Our manager] had kind of started to embed in us before we

even got the official high-performance model.” (Employee 3)

In addition, the knowledge workers were very cognisant of

the fact that the HPWS was being implemented differently and

had different implications across different teams: “we’re not doing

projects like other people in the business…We’ve no chance of

actually getting up to a ‘high’ or an ‘outstanding’ performer… The

feeling

is, dependent on your role, sometimes you don’t have much

opportunity to get above the standard rating which would be

seen to be a good performer. Once you go [to a different role] …,

if you’re involved in projects for example…, you probably have

more opportunity to get up into the higher performance grade.”

(Employee 3)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to better understand the line

manager’s role in the implementation of a new HRM initiative (in

our study, a high-performance model – HPWS). Using Bowen and

Ostroff’s [14] HRM system strength model as our framework, we

analyzed the views and experience of senior management team,

line manager themselves and front-line employees on the topic

of line managers’ implementation of HRM. We found support for

the role of line managers in actualizing HRM through relaying

expectations to employees is paramount, which is consistent with

existing findings [8,12].

In addition, we found the inconsistency of approaches

between line managers in the organization in our analysis of

front-line employee data. In other words, different line managers

implement HRM in different ways, lacking the intra-group

consistency. This aligns with Kilroy and Dundon’s [9] study of

the relationship between front line manager types and employee

behaviors, showing heterogeneity. As we argued in the beginning

of the paper, how line managers implement HRM requires

further attention Brewster et al. (2013). Moreover, how line

managers’ inconsistent implementation affects morale, employee

engagement and perceptions of organizational justice requires

further research and unpacking.

Scholarly Implications

This study contributes to HRM research on the line manager’s

role in HRM strategy implementation in three ways. Firstly, by

focusing on how line mangers implement HRM as perceived by

multiple stakeholders including the senior management team, the

line managers themselves and front-line employees, we provide

a more comprehensive report on how variations across internal

organizational levels exist and may be problematic. Our findings

are consistent with other studies on the increasing important

role of line managers in implementing HRM [12]. The multiple

stakeholders’ views around line managers enable us to better

understand the process of line managers’ implementing of HRM.

Secondly, we adopt Bowen and Ostroff’s [14] conceptualization

on HRM system strength to analyze the role and actions of line

managers, which impact upon the formation of a strong HRM

system. Originally Bowen and Ostroff [14] proposed their HRM

system strength framework as a higher-level construct, which

provides the basis for organizations to develop strong HRM

systems impacting on organizational effectiveness. Understanding

how such a strong HRM system is developed is warranted. Building

on Bowen and Ostroff [14] HRM system strength, we identified the

detailed actions taken by the line managers in order to foster a

strong HRM system and compared this with the information we

received from the detailed interviews. By doing so, we contribute

to the HRM system strength research by providing a useful tool on

the HRM implementation via line managers.

From our case study, we found that intra-level variations, i.e.

different line managers’ implementation of a change initiative in

different ways (that is, inconsistency), influence the perception

of line managers’ successful implementation of an HRM system

across three levels (senior management, line management,

knowledge workers reporting to line managers). We therefore

propose a new and important feature which is the consistency

across line managers into the HRM system strength model, which

advances our current knowledge about HRM system strength.

This suggests that future studies on HRM system strength need to

consider these inter-team variant features.

In terms of methodology, our study adopts a qualitative

single case study using multiple stakeholders, which enriches

existing HRM studies, where quantitative survey methods (more

cross-sectional design) and interviews with line managers

only are dominant. Our study differs from existing quantitative

methods which use complex equations to calculate the interrater

agreement in order to capture the shared and collective

climate [50]. Qualitative research design enables us to explore

what is happening and, more importantly, why. It presents

the perceptions across organizational levels, permitting a

comprehensive overview of HRM system strength as experienced

by the multiple respondents. Rather than simply asserting which

dimensions were prevalent across levels in the organization, the

qualitative study enabled us to unpack, understand, and explain

where shortcomings were apparent.

Finally, this study was conducted in the knowledge intensive

context in a specific country context, namely Ireland. It

contributes to our understanding of HRM in KIFs by examining

the line manager’s implementation of HRM. KIFs are important

for the development of the knowledge-based economy, but the

HRM research in KIFs is limited compared to the large volume

of research conducted on manufacturing firms [51-54] or more

routinized service firms such as banks [55] and call centres [56].

In the existing studies looking at HRM in KIFs [57-60], a survey

method was commonly used. Quantitative research can fail to gain

a real understanding of the specific workings of HRM systems

from the initial phases of system design to implementation, which

can, however, be addressed by using qualitative research.

This proffers a great chance for qualitative research to enrich

our knowledge about, not only what HRM practices are important

for KIFs, but also how they are implemented successfully to lead

the employees to align their individual goals with organizational

goals. The findings in our study provide useful insights for KIFs,

but may also be useful for a much wider range of contexts such as

the service sector that is not limited to the resource of knowledge

Similarly, while our case study focuses on a KIF in Ireland, other

studies may compare our findings across national contexts, in

order to further unpack the Bowen & Ostroff [14] HRM system

strength construct in different contexts [50].

In our study, given the context of the KIF, the role of individual

employees and individual contributors appears under-explored.

The voice of the individual contributor about the change

management process of the HPWS that was introduced in the

case organization was not reflected upon by the other levels

in the organization. We suggest this oversight is relevant for

organizations, particularly KIFs that are constantly striving to

increase competitiveness. To promote a climate of consistency,

the voice of individual contributors and employees needs to be

acknowledged and integrated in a more reflexive way within the

HPWS implementation process.

Given the context of KIFs, it is important to ensure malleability

of the change process and agility to match the process with

the context and individuals involved. In other words, both a

best fit and best practice approach is required, in line with

the bundling of HRM practices to specific departments and

employee needs, cognisant of the cross-over effect this may have

on other departments, comparing their work inputs and reward

outputs internally. Evans & Davis’s [61] model which proposed

the relevance of internal social structures in the performance

outcomes of high-performance work systems is important here.

Implications for Managers

Our study appreciates the senior managers’ promotion of

a change management initiative (e.g. introducing a new HPM

system) and the HR manager’s role in working with senior

managers and other human resources in the organization to bring

about the new practices [62-65]. This importance of these roles

was apparent in our findings. The support of a change initiative

by senior management is crucial in ensuring buy-in from others

in the organization. While the literature has emphasized the

line manager’s role in the implementation of HRM practices, the

directional and exemplary influence of senior management cannot

be underestimated. However, that alone is not enough.

The role of front-line employees, the primary subjects of

the new high-performance management system, in providing

feedback and insight to the system may be under-appreciated

and/or ignored by the other levels in the organization. Indeed, a

top-down - rather than a reflexive, top-down/bottom-up – change

management implementation process was apparent in our study.

We question this lack of inclusion of front-line knowledge workers

in the implementation and feedback process of a new HPWS,

particularly one that directly affects them. There are lessons

for practitioners which our study has brought to light. First,

HRM professionals, who are aware of the important role of line

managers in promoting a strong HRM system in the organization,

need to recognize and develop measures to counter the variation

in line manager’s implementation processes, depending on the

respective experience, skillset and functional area of the line

managers in question. Line managers need to implement HRM

in a distinctive, consistent and consensual way to develop HRM

strength [14], where employees share collective perceptions of

HRM within the organization.

Therefore, in implementing HRM practices, HRM professionals

need to pay particularly close attention to the promoting stage among line managers, where communication and consultation

with line managers is pivotal. This is supported by our finding

that line managers experience less surety in terms of rationalizing

why HRM models are required and being implemented. For line

managers, they need to work closely with HRM professionals

to share their opinions on whether the intended HRM practices

are relevant to their direct employees’ needs. In communicating

with employees, line managers need to take extra care with

interactional justice and demonstrate that they are in accord

with the HRM department and top management, particularly in

KIFs where employees are aware of how other teams are being

managed [66-69].

Limitations and Future Research

This study was exploratory and examined the implementation

of a high-performance model. It aimed to better understand the

process of line manager implementation of a strong HRM system.

It contributes to theory and practice in many ways, primarily in

providing a more nuanced understanding of the line manager’s

role in the implementation of a strong HRM system in a knowledgeintensive

firm. Nonetheless it does have some limitations. It is

based on a single organization operating in one industrial sector,

on a small sample size, in a specific country context [70-73].

The paper set out to present collective insights across

organizational levels, but we acknowledge that it is difficult to

generalize these findings. As was presented in both the literature

review and the findings from the interviews conducted, the highperformance

model is multidimensional, and it is influenced by

internal and external factors. Its success is gauged not in the

short-term but in the long-term. Longitudinal studies including

diary entries across organizational levels over the implementation

period of a new HRM model would be very useful in further

research, in providing detailed data of the nuances across

organizational levels over time [74-76].

The data for our study was collected entirely from one

organization. Although the richness of the qualitative data

facilitated unpacking the line manager’s role as perceived

across organizational levels, the findings shared here need to be

empirically tested in a larger sample and other organizations/

KIFs to see if they can be generalized. In the data collection stage

of the study, the sample was selected based on the first author’s

own network which might have resulted in respondents’ bias.

However, the quotes and interviews that were analyzed did show

heterogeneity across the perceptions of the HPWS implementation.

A future research avenue would be to further consider our

extension to the Bowen & Ostroff [14] model (including a crosslevel,

intra-level and looped approach) quantitatively, through

deliberately separating out different levels [77].

We acknowledge that the interview data from the case

organization considered in this paper is limited, due to the small

quantity of interviews conducted. However, small sample sizes are

usual in qualitative research and this research undertaking sought

to consider HRM system strength components [14] through coding

the interview data with this model in mind. While this paper has

drawn on only a limited number of interviews with employees

across the organizational levels at the knowledge intensive case

firm, it does provide a snapshot across organizational levels of how

key players in a change initiative experienced the process. Future

research studies could focus on a level and gather more interviews

at that level in order to develop further knowledge about how a

change initiative, the introduction of a high-performance model,

is perceived and implemented at a level within the organization

[78-81].

In qualitatively coding the data under the Bowen & Ostroff

[14] features, it became increasingly evident to the researchers

that the boundaries between some of the features and metafeatures

according to Bowen & Ostroff’s [14] framework overlap

[82]. There were quotes that were coded under both visibility (as

everybody was talking about it) and understanding (which aspect

of the model resonated with the individual employee). While this

may be considered a limitation, the authors did not find that it

limited the analysis, but rather that it supported the complexity

and comprehensiveness of the model. As outlined earlier in

this section, longitudinal studies on the HRM system strength

construct in relation to the introduction of HRM initiatives

within organizations would be particularly interesting for further

research in this area. Such a study could further unpack the HRM

system strength model in practice [83,84].

Conclusion

This study extends our understanding of the line manager’s

role in HRM implementation via a single case study of a large

knowledge intensive firm based in Ireland. Employing Bowen and

Ostroff’s [14] HRM system strength model, this study qualitatively

unpacks how line managers implement HRM initiatives, as

perceived by senior management, frontline employees and the line

managers themselves. Line managers’ implementation of HRM is

found to be aligned with all features of a strong HRM system.

Both senior management team members and front-line

employees (knowledge workers) in our study emphasized

the importance of line managers’ implementation of HRM in

promoting a strong HRM system. However, concerns are raised

about the inconsistency of implementation practices among

line managers. How organizations, senior managers and HRM

professionals support and develop line managers consistently in

order to lead to employees’ shared perceptions and experience of

organizational HRM is an interesting and important question for

future research, particularly in the context of KIFs where agility

and flexibility across departments is essential.

Comments

Post a Comment